With its central role in the formation of the Danish kingdom and its physical size, the Viking-Age ring fortress, Nonnebakken, is one of Odense’s largest and most significant ancient monuments. This has led to the fortress, together with four other contemporary Danish ring fortresses, being included in a joint application to become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The application was submitted in January 2021, and if all goes well, the fortresses will be designated a World Heritage Site by July 2022. In the following, you can read more about the investigations at Nonnebakken and the dissemination of the research.

The location of the Viking-Age ring fortress, Nonnebakken, in the centre of Odense, close to Hunderupvej and the Odense River. Outer ring: moat. Inner ring: rampart.

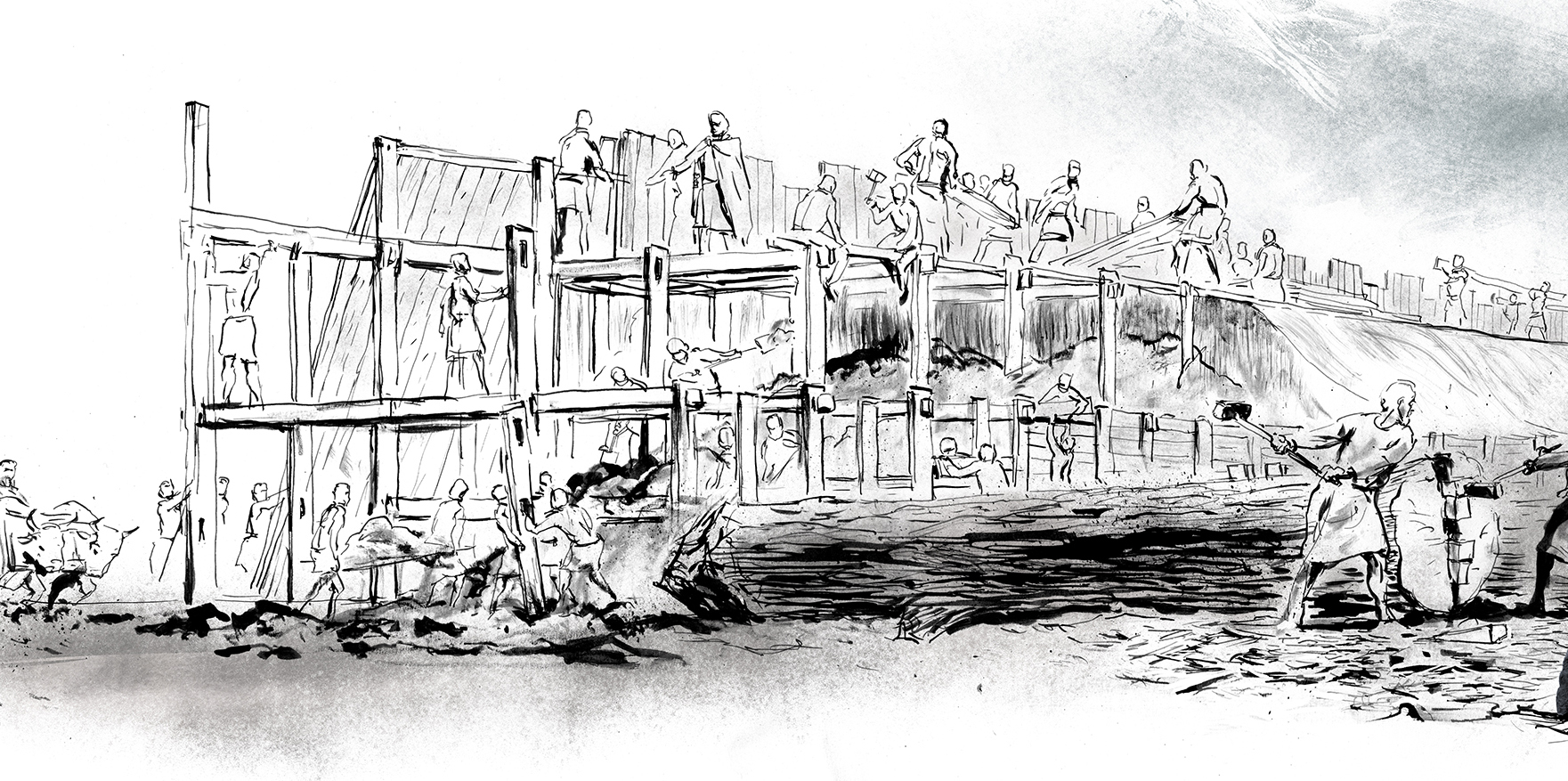

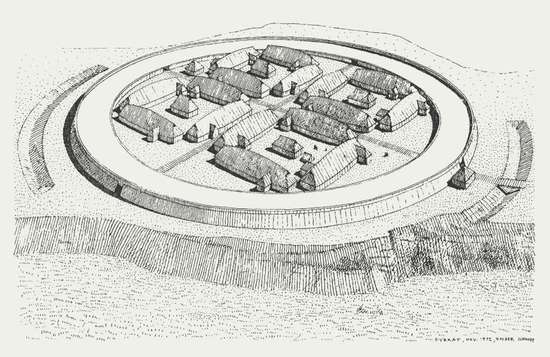

Nonnebakken is centrally located in Odense and, in the Viking-Age, it was occupied by a huge circular fortress with an outer diameter of 180 m. The fortress had a 9 m wide moat which was at least 4 m deep and a wooden clad rampart which would have been approximately 15 m wide and possibly up to 5-6 m high. At each of the fortress’ four cardinal points, there was a covered gate and these were connected by two axis roads which divided the fortress into quadrants. Each quadrant contained a block of four longhouses. A road measuring 1.6 m wide, ran around the inside of the rampart.

© Reconstruction drawing of the ring fortress Fyrkat, near Hobro. Drawing: Holger Schmidt.

The ring fortress was established around the year AD 980 and is attributed to King Harald Bluetooth’s group of ring fortresses. They were all built in the 970s and 980s as a clear indication of the ambition to unite the Danish kingdom and protect against external enemies. The ring fortresses are all constructed using the same geometric principles and, alongside Nonnebakken, include Aggersborg near Løgstør, Fyrkat near Hobro, Trelleborg near Slagelse and Borgring near Køge. The ring fortresses seem to have all had very short lifespans of around 10-15 years. Nonnebakken literally translates into English as ‘The Nun Hill’ and gets its name due to the fact that a nunnery was located on the Viking-Age mound in the 12th century. Today, it is possible to make out the levelled rampart, on which the Odd Fellow Lodge now sits, and a few other traces of the fortress within the landscape, whereas other remains, though well preserved, are hidden beneath the modern city.

Nonnebakken can be found on several historical maps, including the oldest map of Odense, Braun’s prospect from 1593, where the remains appear as two crescent-shaped ramparts.

© Excerpt from Braun’s prospectus from 1593, the oldest map of Odense. The map shows Nonnebakken as it looked at the time. Note the two openings in the rampart.

In depictions dating back to the end of the 19th century, the rampart can still be seen standing several meters high. However, in 1909, a construction team removed large parts of the northern rampart and used the material to fill in a branch of the Odense River. Today, the site exists as a distinct elevation in the landscape leading down to a low-lying area by the river. Over the years, from the 18th century onwards, a number of Viking-Age artefacts have been recovered from several small archaeological investigations carried out in the area around Nonnebakken.

Over time, a lot has been learnt about the site. Nevertheless, up until as recently as 2015 when new, targeted research techniques were employed in the form of excavations, georadar surveys and drilling, Nonnebakken has had a fairly vague status as a mostly ruined “possible ringfort”. However, new research has established that Nonnebakken is one of Harald Bluetooth’s ringforts and – probably just as important – that there is really good preservation at the site with a rampart that is still at least one meter high with a well-protected original ground surface within the defences.

© A cross section through the rampart at Nonnebakken. Towards the base, the yellow subsoil can be seen and just above it lies a dark layer of buried topsoil. On top of this original topsoil is an orange layer of solid clay followed by a yellow and grey lensed layer which are the remains of the turf-built rampart. At the very top are layers from more recent times when material was used to level the ground surface. Photo: Mads Runge. Drawing: The magazine Skalk.

The good preservation conditions mean that the site has great research and exhibition potential and therefore Nonnebakken plays an important role within research projects such as The Origins of Odense, Nonnebakken – The Viking-Age Ring Fortress in Time and Space and From Central Space to Urban Place.

Currently, onsite information about Nonnebakken is limited to three signs located close to the ring fortress and the course of a section of the rampart marked onto the pavement in the schoolyard at the privat e scholl, Giersings Realskole. However, the museum is working with Odense Municipality to rectify this and create a much more engaging way to convey information at the site. With this in mind, the landscape architect Erik Brandt Dam and the design company JAC Studios have developed a concept for marking sections of the rampart on the area of grass in front of the Odd Fellow Lodge and developing an information point in the form of a 1:30 scale model of a ring fortress north of here. Provided that the necessary funding is obtained, the project will be carried out in 2022/2023.

© An artist’s impression of the proposed marking of the rampart surrounding Nonnebakken. Erik Brandt Dam Arkitekter & JAC Studios.

It is the museum’s ambition that the archaeological display at Nonnebakken should be linked to other, planned dissemination points regarding early Odense. These initiatives are united under the heading Knud’s Odense – the City of the Vikings which includes a so-called ‘Viking route’. The route begins at the museum at Møntergården, where the original artefacts and their detailed stories can be found, before moving on to the site of the former church at St. Alban’s Priory, where the last Viking King, Knud the Holy was murdered. The route then leads up to St. Knud’s Church, where Knud the Holy and his brother Benedict lie in rest in fantastic, gilded shrines with unique 1000-year-old textiles.

In relation to the other sites included in the application for World Heritage status, the connection between Nonnebakken and the city is extremely interesting and important to focus on. Nonnebakken is the only one out of the five ringforts that, in the Viking-Age, developed into a city, and it is only at Nonnebakken that Harald Bluetooth’s ambition to unite the kingdom has had a lasting impact. This can be seen by the fact that Odense, since the establishment of Nonnebakken, is further developing into Funen’s capital with its function as the bishop’s seat. The cities and the church have played an important role in the formation of the kingdom. The history of Nonnebakken and Odense thus adds extra dimensions to the overall story of the five ring fortresses and their significance.