Looking back upon his few but eventful years as a ballet pupil and supernumerary at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen, H.C. Andersen recalled that he stood „den hele Formiddag ved den lange Stok og strakte Been, lærte at gjøre Battement, men uagtet min Flid og gode Villie lovede jeg ikke meget for Dandsen.“[1] There is no reason to doubt Andersen’s own modest evaluation of his dancing ability. However, although his youthful efforts to conquer the Royal Theatre stage are in one sense mere footnotes to the history of his later achievement, they continue to arouse our interest because for the fifteen-year-old Andersen, newly arrived in the capital and needing guidance as desperately as ever a young author did, they constituted an experience of the greatest importance. – As Denmark’s leading connoisseur of Anderseniana, dr. Topsøe-Jensen, has wisely remarked: „Smaa Træk kan undertiden sige noget, naar det gælder store Mænd.“

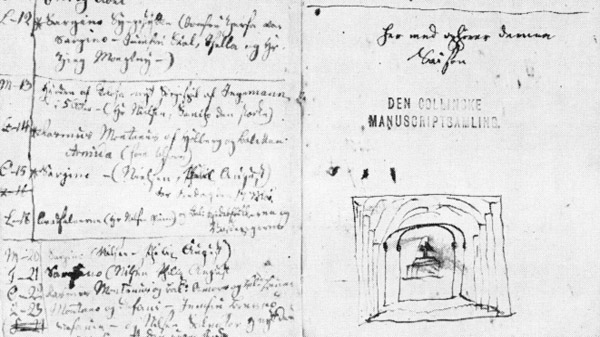

H.C. Andersen recaptured the atmosphere of the ballet school and the milling backstage life he experienced in such pearls of storytelling as Moster and Lykke-Peer. To gain an accurate idea of the productions in which Andersen actually did appear at the Royal Theatre, meanwhile, one may best turn to the one-hundred-and-fifty-year-old historical documents themselves, several of which have lain unnoticed in the Theatre’s archives. Also aiding in the search is a small „theatrical diary“ in Andersen’s handwriting, begun on 4 September 1820 and preserved in the Royal Library’s Collinske Samling.[2] In this diary Andersen listed the repertoire performed at the playhouse on Kongens Nytorv in 1820 and 1821, marking each production that impressed him with an asterisk and noting those momentous occasions on which he himself trod the boards as an extra.

On 14 September 1820 the Royal Theatre performed the popular one-act singspiel, Les deux petits Savoyards (De to smaa Savoyarder), on a bill with Carl Schall’s one-act comedy, Tro Ingen for vel, and a comic divertissement by Mlle. St. Clair, and Andersen was able to note in his theatrical diary his stage debut at Kongens Nytorv – as „en af Markeds-Folkene.“ From Mit Livs Eventyr one recalls that he trouped in „with pounding heart“ together with the others, pupils and stagehands, who served to fill out the market scene in d’Alayrac and Marsollier’s operetta, only to be frightened offstage again by „one of the singers“ – identified in Levnedsbogen as the actor Johan Daniel Bauer – who tried to make Andersen’s obviously ungraceful appearance the butt of a joke by congratulating him publicly on his debut.[3]

Far less traumatic was Andersen’s next appearance, on 25 January 1821, in the role of „a musical servant“ in Galeotti’s colorful pantomimic ballet about a young, passionate girl who is mad from love, Nina, eller Den vanvittige af Kærlighed. The Royal Theatre’s maskinmester protocol provides some characteristic information about the general duties of the extras in Nina: „10 Stk. hvidlaquerede Stoele med Skraaesæder bæres ud fra Pavillionen … af Statisterne og stilles langs med Gitteret. 4re hvide Voxfakler leveres til Statisterne.“[4] H.C. Andersen’s special task in this ballet, meanwhile, was to impersonate one of the two musicians who play for Nina and soothe the distraught girl with a melody that recalls her lover. The two musicians were placed farthest forward on the stage, and Andersen was deeply flattered that the bewitching Anna Margrethe Schall, who played Nina, paid him particular attention – „rimeligviis har jeg gjort en meget komisk Figur,“ he later admitted.[5]

On April 12th of the same year, Andersen appeared as one of the trolls in Carl Dahlén’s four-act heroic ballet, Armida – a celebrated appearance that has since enjoyed the attention of such eminent theatre-historians as Robert Neiiendam and Torben Krogh.[6] The action of Armida, based on Gluck’s opera, takes place during the First Crusade; the seductive Saracen sorceress Armida ensnares the crusader Rinaldo, without whose help Jerusalem cannot be freed. Rinaldo lives intoxicated with love on Armida’s enchanted island until he is freed from the spell by a colleague, the crusader Ubaldo, who leads his wayward friend back to battle. Wearing a „hideous mask“ as one of Armida’s eight trolls, H.C. Andersen’s first stage business was to seize Rinaldo’s sword and shield, while a frightful storm and a bolt of lightning destroying Armida’s altar brought down the curtain. By no means less spectacular was the appearance of Andersen in the finale. Here the trolls are conjured out of the ground and gather on a cliff together with Armida, who hurls a bolt of lightning at Rinaldo’s departing ship. The cliff collapses with the trolls „falling in various violent positions“ – Bournonville later recalled that Andersen fell headlong out of a crevice![7] The curtain fell as Armida ascended in a fiery car drawn by dragons and the trolls sank back into the ground.

Despite Claus Schall’s music and the ballet’s many spectacular effects, meanwhile, Armida proved unsuccessful. Nonetheless, it did provide Andersen with both a delightful „nimbus of immortality“ — the sight of his name in print for the first time on the program – and a vivid introduction to the kind of spectacular theatricality so typical of the romantic theatre at this time. In his first novel, Fodreise fra Holmens Canal til Østpynten af Amager i Aarene 1828 og 1829, he recalled, in an impressionistic, Hoffmann-like vision capturing the essence of nineteenth-century theatre, the very effects he had seen at close range on stage in Armida a few years before:

Dækket rullede op, og man saae ind i en uhyre

Caleidoskop, der ganske langsomt blev dreiet

rundt. Klipper med Vandfald, brændende Byer,

Skyer med Ildregn, og strandende Skibe, styrtede

brogede imellem hinanden.[8]

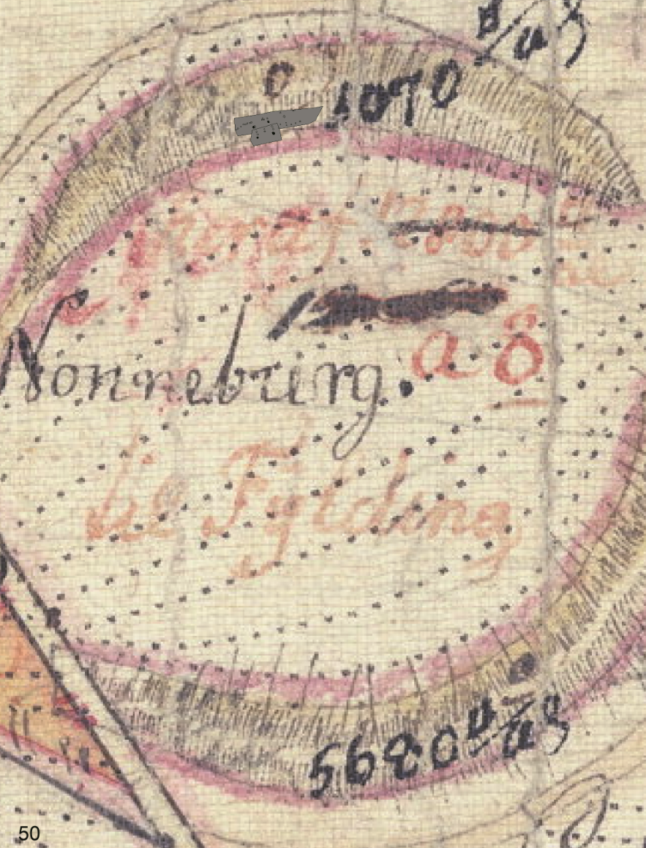

After transferring to the Royal Theatre’s Opera Academy in the 1821/22 season – the final phase in his fruitless struggle to become an actor -Andersen figured in the chorus of a number of other productions. The fragment of his theatrical diary that survives from this season mentions roles as ,,en Bjarkebeiner“ in Axel og Valborg, „en Page“ in Maskarade, „en Bramin“ in Simon Mayr’s singspiel, Lanassa, and „en Drabant“ in Zoraïme og Zulnar, written by the celebrated French composer Boieldieu, whose better-known work, La dame blanche (Den hvide dame), had so decisive an influence on nineteenth-century Danish theatre.[9] To test the accuracy of Andersen’s diary and other recollections, meanwhile, one may turn to the archivalia of the Royal Theatre, particularly those costume lists which have survived for the productions in question, in search of the great poet’s name among the supernumeraries. For instance, although he asserts that he „drew the triumphal car“ in Zoraïme og Zulnar,[10] two separate costume lists, each dated January 1821, fail to indicate that H.C. Andersen actually did appear among the numerous „Drabanter“ or anywhere else in this production. More rewarding for our purposes, however, are several other documents that have come to this author’s attention in the Royal Theatre Library.

It has previously been assumed that the appearance of Andersen’s name in the Royal Theatre archives from this early period was limited to a single page from the ballet protocol for Armida, where his name shares the spotlight with that of another illustrious pupil of the ballet, Johanne Luise Pätges – later fru Heiberg.[11] A more patient search among the Theatre’s costume lists proves otherwise. Hence, in a list entitled „Dandsepersonalet i Intermediumet i Maskarade,“ one discovers H.C. Andersen’s name and learns that on this occasion he danced „an English dance and waltz“ with one Jfr. Bolstrup. Similarly, a costume list from 1821 for Thaarup and Schulz’s Danish pastoral idyl, Høstgildet, contains Andersen’s name and allows us to visualize the poet among eight „Peasants“ who were dressed in bright rustic costumes, variously colored scarves, blue and white woolen stockings, and peasant boots.

Perhaps the most informative Andersen item among these documents, however, is the costume list for Lanassa, an exotic operetta set in East India during the time of Henri IV. This list provides an interesting correction to Andersen’s highly entertaining but rather exaggerated account of this production in Levnedsbogen. Entitled „Dragter og Requisiter til Lanassa,“ the ten-page document in the Royal Theatre Library lists two familiar names among the seven „Bramins“ who graced the chorus: H.C. Andersen and actor-historian Thomas Overskou. From Andersen’s youthful autobiography one remembers his vivid description of the embarrassing Bramin costume he wore:

… snevert kjødfarvet Tøi over hele Kroppen,

kun et lille Belte, ellers hele Ryg og Bryst

nøgent. Haaret afraget paa en lille Pidsk nær,

vi saae skrækkelige ud.[12]

He „had looked like a flayed cat,“ Princess Caroline allegedly told him afterwards, while actor N. P. Nielsen – who was in reality not among the seven chorus Bramins but who played Zorai, Lanassa’s brother – resembled „a great, bald hog“! The truth, meanwhile, was both a good deal less bare and less drastic. The Theatre’s costume list indicates that Andersen’s Bramin costume in Lanassa clearly belonged to the category of standard „exotic“ stage attire: „Røde pantalons, Trøier og Beenklæder, guult Tunikker, guule Draperier. Skoe af ufarvet Læder. Guule Turbaner. Guule Liv Baand.“

Although H.C. Andersen’s brief career as „Royal Theatre actor“ may have included other productions during this period, no record of his name or his function has survived in the archives of the Theatre. As a dramatist with no fewer than twenty-one original plays and opera libretti produced at Kongens Nytorv, his name naturally appears frequently in the Theatre’s records after 1829; but his dismissal from the chorus in June 1822 put an abrupt period to all ambitions of becoming an actor. It was obvious to those having eyes to see that his unique talent lay in another direction. „Hans ranglede Figur og kantede Bevægelser syntes imidlertid mindre skikkede til Dandsen,“ wrote Bournonville of his first impression of the poetically inclined ballet pupil, „og min Fader spurgte ham derfor, om han ikke skulde foretrække det reciterende Skuespil, hvorpaa den unge Fyr udbad sig Tilladelse til at fremsige et af sine Digte. Dets Indhold mindes jeg ikke, men saameget er vist, at jeg strax fik Indtrykket af noget Genialt og langtfra at finde ham latterlig, forekom det mig, som om han snarere vilde have os tilbedste end vi ham.“[13]

This essay, in somewhat altered form, appeared as a portion of the introduction to the author’s doctoral dissertation, The Performance of H.C. Andersen’s Plays at the Royal Theatre, 1829-1865, presented to and accepted by the Faculty of Yale University, Graduate School of Drama, in June, 1967.