The aim of this article is to consider two partly overlapping types of children’s literature and Hans Christian Andersen’s place in relation to them.

They are:

An example of the first is Andersen’s ‘The Nightingale’, of the latter ‘The Travelling Companion’, whereas the two coexist in stories like ‘The Elfin Mount’.

In the following, I propose to trace these types back to their origins, as far as we can determine them – for I am sure that both types predate written literature – and to look at Andersen’s contribution to these genres, and at the legacy he left to later writers, particularly in Denmark. Both types were as a matter of course incorporated in the category of “Children’s Literature”, when it began to develop in the 17th century. But many writers, and certainly Andersen, wanted their tales to appeal to both young and old. In the following, among other things we shall look at the extent to which imitators of Andersen succeeded in preserving this double appeal.

Let me observe in passing, that in a context like the present, it would of course be natural to discuss Andersen’s influence on English writers. But I have already done so, see (VHP: 2003), which demonstrates this influence particularly on Oscar Wilde’s children’s stories and on the American writer Horace Scudder. This is why I shall here concentrate on Andersen’s place in relation to Danish children’s literature, although a couple of English writers are also mentioned.

The roots of this genre, where animals think and speak, but otherwise behave like humans in a normal, everyday world, and where, as a rule, supernatural powers are not invoked, are in antiquity. The purest example is perhaps the classical fable a la Aesop, where the characters behave in ways traditionally associated with the various animals – the fox is cunning, the lion proud and bold, the wolf ferocious – but otherwise go about their business in ordinary ways. If the mouse frees the lion from a net, it does not do so by means of magic, but by applying its teeth to the task in hand.

Extended narratives of this kind became popular in the middle ages, especially stories about foxes, a genre that lasted on well into the romantic age (e.g. Goethe’s Reinicke Fuchs (1794) translated by Oehlenschläger (Reineke Fos, 1806). The type that Andersen imitates in ‘Soup on a Sausage-Peg’, among others, is 18th century in origin and follows the neoclassical precept of mixing the useful with the entertaining. A good English example of this genre is Mrs. Trimmer’s Fabulous Histories (Cf. VHP: 2004).

Sarah Trimmer (1741-1810) began her career in the 18th century with attacks on the belief in fairies, a sore point with many educators at the time. But she also wrote a delightful book of Fabulous Histories (1786), later known as The History of the Robins. It describes the life of a little family of robins and their relation to the human family in whose garden they live. Like the real children in the story, the young robins are very human and frequently naughty, and in spite of some moralizing the deservedly popular story, which was reprinted throughout the 19th century, is fanciful and charming. But it should be noted that the book is called Fabulous Histories and according to Mrs. Trimmer’s preface should be considered as “a series of FABLES, intended to convey moral instruction … and recommend universal Benevolence” (1786: x-xi).

Indeed Mrs Trimmer took her morality so seriously that in order to gain a point here she transgressed against one of her other maxims, that children’s books should provide useful instruction: when a mockingbird is rather incongruously introduced into the English garden, we are told in a footnote (1875: 159) that “The Mocking-bird is properly a native of America, but is introduced here for the sake of the moral,” the moral being close to that of Andersen’s Nightingale, i.e. that natural singing is to be preferred to artificial imitation.

I am not postulating the existence of a direct link between Trimmer and Andersen or other Danish writers, but merely want to point out that they belong to the same tradition and that there are many similarities between their narratives.

Mrs. Trimmer’s book has two overlapping universes – one of birds and one of men, and is thus very similar to K.H. With’s Danish classic Musebogen or Musene i Rynkeby Præstegård (The mice in Rynkeby parsonage – 1866). I think that With’s handling of the mice resembles Andersen’s in ‘Soup on a Sausage-Peg’, which had appeared 8 years before (1858). But they both hark back to 18th century narratives like the one described above, and where Andersen takes his anthropomorphism so far that the realm of the mice is organized with a king, With’s mice just form a family, like that of Mrs. Trimmer’s robins. In Andersen’s story, indeed, the mice have largely replaced the humans, whereas in With’s as in Trimmer’s, both animals and humans appear. Both can speak and reflect, and the mice understand the humans, but they do not answer them, so there is no communication between mice and men.

This story is old-fashioned also in its insistence on the unpleasant facts of life, such as hunger, danger and death: a son of the family, who never heeds the admonitions of his parents, dies in a trap; and the narrative is interspersed with short bed-time stories, which mother mouse tells to her children, including the fable of the mice that would bind the cat and that of the lion and the mouse.

Interaction of animals and humans, which is frequently found in folktales (although the animal here is often a human in disguise – cf. Grimm (‘The Frog Prince’, the fox in ‘The Golden Bird’, and ‘Puss in Boots’)) is characteristic of Andersen’s Nightingale. In a less developed form it often occurs, as when the narrator in ‘Thumbelina’ tells us that he has learned his story from the swallows.

It is probably expedient to deal with the clearest example of Andersen influence here, Harald Bergstedt’s Store-Grisen (The big pig – 1941), although Andersen’s influence here is diffuse and includes elements from the supernatural tales, whereas Bergsted’s story is primarily didactic.

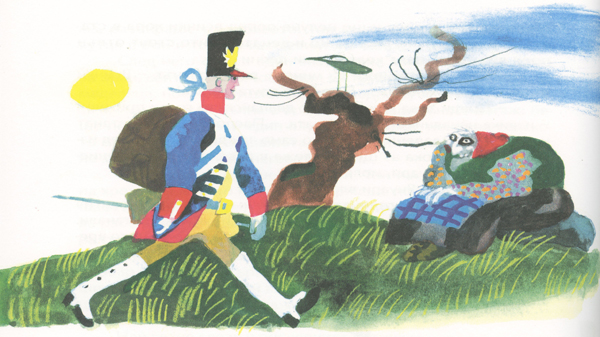

It starts in the tenant’s field, where the swine are rooting in the mud, but have plenty to eat. The biggest of them in fact has eaten so much that he has developed longings for other things, and when a starving vagabond says that he would wish that he could change places with the pigs, Big Pig tells him to cut a wand off a certain willow, smack him with it and say “Kvit, kvit, Skindet er mit” (it’s my skin, and I want in). No sooner said than done, and the vagabond can now feast on the pig feed while Big Pig like a very fat and dirty vagabond marches towards the nearest town. Before the change, however, the vagabond has stipulated that Big Pig is to look after his family of starving children, and he has promised to do so.

Once in the town, Big Pig discovers that he is not very popular. He thinks that it is because he is dirty and clothed in rags, but really it is because he has no money. However, near his old home the pig has discovered an old robbers’ den full of gold coins, so he takes a wheelbarrow, goes back, and returns with a barrowful of gold. Now he encounters no difficulties, and is quickly launched on a splendid career as a capitalist and bon vivant – for his appetite has not deserted him. But he has forgotten the starving kids, so the vagabond-/pig pays him a couple of visits at inopportune moments to remind him of his obligation. Nothing is done, however, the main reason being that there are so many starving kids in the country that the pig despairs of being able to find the right ones (and of course the idea of doing something for them all does not occur to him). In the end the vagabond manages to get a message to his children, who swear to revenge him. It is not easy, for Big Pig is now surrounded by servants and bodyguards, but the youngest and smartest manages to get close enough to smack the pig/man with a wand, so that his father can be restored to his original form, whereas Big Pig runs away and is never heard of again.

The most obvious Andersen influence on this story is from “The Tinder-Box”. The way the pig obtains his gold and takes it to the fancy hotel where he wants to stay is obviously influenced by that story, as is the changing behaviour of his surroundings according to his wealth or lack of same. But we can go further than that and claim that the whole attitude to wealth and to social stratification is related to what you find in Andersen stories like “Everything in its Right place” and “The Gardener and the Family”. Only Bergstedt is sharper than Andersen and his writing is obviously informed by social indignation, if not by socialist ideology.

But the similarity also extends to the way the story is presented. The opening, for instance, is reminiscent of that of some of Andersen’s stories that were “told to the children”:

Hør nu her en mærkelig Historie. Den er saa slem, saa man maa sidde godt fast paa Bænken for ikke at gaa bagover.

Nu kommer den.

Der gik en flok Svin paa Forpagterens Mark. …

Now listen, for this is a strange story. It is so horrible, that you have to sit up straight not to be completely bowled over.

Here goes.

There was a flock of swine in the tenant’s field….

The humour is more sarcastic than Andersen normally allows himself to be – closer perhaps to Orwell than to Andersen. But the pig’s recurrent reaction to anything from flowers to poetry, “Øf, er det noget man kan æde”? (oink, can you eat that?) is not unparalleled in Andersen, where a similar callousness is often seen in the late tales, for instance in “The Duckyard”, where the drake’s comment on the murder of an unoffending sparrow is:

“Lad os nu tænke paa at faae Noget i Skrotten!” sagde Andriken, “det er det Vigtigere! Gaaer et af Spilleværkerne i Stykker, saa have vi nok alligevel!”

“Let us now think about getting something in our stomachs,” said the Drake. “That’s the most important thing. If one of our playthings is broken, why, we have plenty more of them!” (Hersholt)

Harald Bergstedt has been unduly neglected because of his conviction after World War II for pro-Nazi activities. But he has written what is probably the best Danish children’s song (strangely reminiscent of Andersen’s “Det døende Barn” (the dying child)), “Solen er så rød, mor” (how red the sun is, mummy), in addition to this little masterpiece, which is truly a work of genius. His work is very difficult to come by – it is almost as if the libraries had had a purge after the war. There is further information about Bergstedt in Nilsson (2004).

Supernatural elements belong to the folk tradition and were frowned upon in 18th century educational tales. We are not here concerned so much with magic realism, which can be traced back to the folk tradition and is very characteristic of Andersen right from the start – think of “Little Ida’s Flowers” and “Ole Luckoie” – but with tales where supernatural beings and magic events fill up a considerable part of the narrative. On one level “The Nisse at the Grocer’s” can be read more or less realistically as a story about idealism versus (necessary) materialism: “Vi andre gaae ogsaa til Spekhøkeren – for Grøden.” (We all of us visit the grocer for the sake of the porridge.) But the protagonist is of course a Nisse, and as such outside realism in the ordinary sense.

How does Andersen’s use of the supernatural differ from that of the folktale? Well, Andersen, following the German Kunstmärchen, is ironic – Grimm is not. In the folktale, the supernatural is surrounded with awe; not so in Andersen. Cf. “The Nisse at the Grocer’s”:

Da det blev Nat, Boutiken lukket og Alle tilsengs, paa Studenten nær, gik Nissen ind og tog Madammens Mundlæder, det brugte hun ikke naar hun sov, og hvor i Stuen han satte det paa nogensomhelst Gjenstand, der fik den Maal og Mæle, kunde udtale sine Tanker og Følelser ligesaa godt, som Madammen, men kun een ad Gangen kunde faae det, og det var en Velgjerning, for ellers havde de jo talt hverandre i Munden.

When it was night, and the shop was closed and all were in bed, the Goblin came forth, went into the bed-room, and took away the good lady’s tongue [Danish: Mundlæder]; for she did not want that while she was asleep; and when-ever he put this tongue upon any object in the room, the said object acquired speech and language, and could express its thoughts and feelings as well as the lady herself could have done; but only one object could use it at a time, and that was a good thing, otherwise they would have interrupted each other. (Dulcken)

A mixture of supernatural creatures and personified animals, combined in ways that one would hardly find in real folktales, occurs in Andersen’s “The Elfin Mount”, which has provided inspiration for a more recent children’s writer, Dines Skafte Jespersen, with his enormous series of stories about “Troldepus”, a very lively and charming little troll boy.

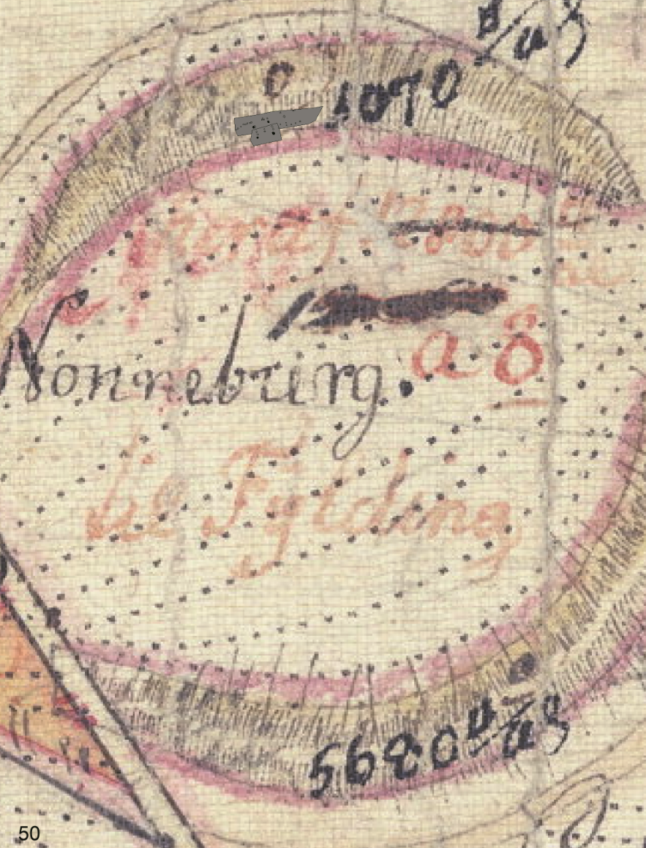

“The Elfin Mount” is about a party which is to take place in a barrow in the forest; the whole arrangement is like a party given by members of the Copenhagen bourgeoisie that Andersen knew so well, with a few touches from the court, with which he was also fairly familiar. The fun consists partly in the menu, which is such as elfs and trolls would enjoy (see below), partly in the reactions and interrelations of the characters which though supposedly supernatural are in fact very human. Listen e.g. to the following bit of reportage, which is a clever caricature of the kind of thing you might easily witness on TV today when they are busy commenting on some event in the royal family:

Elverpigerne dandsede allerede paa Elverhøi, og de dandsede med Lang-schawl vævet af Taage og Maaneskin, og det seer nydelig ud for dem, der synes om den Slags. Midt inde i Elverhøi var den store Sal ordenligt pudset op; Gulvet var vadsket med Maaneskin og Væggene vare gnedne med Hexefedt, saa at de skinnede som Tulipanblade foran Lyset. I Kjøkkenet var der fuldt op med Frøer paa Spid, Snogeskind med smaa Børnefingere i og Salater af Padehatte-Frø, vaade Musesnuder og Skarntyde, Øl fra Mosekonens Bryg, skinnende Salpeterviin fra Gravkjælderen, Alt meget solidt; rustne Søm og Kirkerude-Glas hørte til Knaset.

The elf girls were already dancing on the elf-hill, and they danced with shawls which were woven of mist and moonshine; and that looks very pretty for those who like that sort of thing. In the midst, below the elf-hill, the great hall was splendidly decorated; the floor had been washed with moonshine, and the walls rubbed with witches’ salve, so that they glowed like tulips in the light. In the kitchen, plenty of frogs were turning on the spit, snail-skins with children’s fingers in them, and salads of mushroom spawn, damp mouse muzzles, and hemlock; beer brewed by the marsh witch, gleaming saltpetre wine from grave cellars: everything very grand; and rusty nails and church window glass among the sweets. (Dulcken)

In other words, we see here how Andersen builds up a world parallel to the real one, thus showing reality in caricature, but still in recognizable form. As we shall see, this is also very much the approach of the early Troldepus-books.

Dines Skafte Jespersen (1905-88) was a teacher and a writer with many books to his credit, most of them for children.[1] His first book in what was to develop into a series of 41 volumes of long stories or short novels was Troldepus fra Troldhøj (1943). This, as the following volumes, was first issued as a large-size, thin, illustrated picture-book in carton, but for the last 30 years or so the books have appeared in a small format, however, with the original illustrations by Karl Tornby. Jespersen went on producing new volumes right up to his death in 1988. However, for elderly people like myself, Troldepus is associated with the 40’s and 50’s.

Like Andersen, and certainly inspired by him, Skafte Jespersen builds up a parallel universe, not unlike that of Tolkien in The Hobbit. The trolls can assume any shape they like, but the father of the family prefers to be the size of a small man. The barrow is lit by iridescent cones, as in Andersen’s “Travelling Companion”; but otherwise, the trolls live a normal, mid-20th century family life in a nuclear family with father, mother, a boy – our hero – and a little girl. There is a little magic involved (invisibility when you put a white stick into your mouth, and the ability to fly through the air when you brandish a magic wand), and the grown-ups prefer to sleep through the winter, like the hedgehogs; but mother troll in true human fashion organizes a spring cleaning, much to the disgust of the male members of the family, and not unlike the kind of thing I remember from my own home at the time. Altogether, the home of the trolls functions in a way familiar to contemporary young readers.

There is a lot of interaction with the animals of the forest, who can all talk and many of which are individualized, and in later volumes Pus goes on expeditions to a neighbouring farm and even to the Zoo in Copenhagen to meet more animals. (Later still he goes abroad to see more of the world and thus introduce his young fans to it – I’m sure Jespersen must have taught geography!).

In his use of animals – which are invariably anthropomorphized – Jespersen is inspired by the Danish writer Sven Fleuron, who wrote many books with fairly accurate descriptions of the lives of various animals in them, but always seeing the animals in human terms.

The main difference between the Troldepus books and Andersen’s stories with supernatural beings in them is that Jespersen sticks to the perspective of providing entertainment – and some light instruction – for children. And this is perhaps a good starting-point for a conclusion: Andersen has had several imitators, also within traditions not touched upon here – how about Selma Lagerlof’s Niels Holgersen and Andersen, for instance? – but not all imitators have been able or willing to preserve the double perspective of the master, talking to adults through seemingly naive stories for children. However, it is certainly possible for gifted artists to do so, as proved by Oscar Wilde and, in the present context, especially by Harald Bergstedt.

Andersen og tradition: Dyrefortælling og trylleeventyr

I denne artikel diskuteres to delvis overlappende litterære former og H.C. Andersens forhold til dem. Det drejer sig om dyrefortællingen med personificerede dyr, og eventyret med overnaturlige væsener, hvis grundform er kendt som trylleeventyret. Andersen ‘arvede’ begge disse former og brugte dem, ofte i modificeret form og ikke sjældent i kombination. Men hans eventyr kom så igen til at danne forbillede for andre forfattere. I artiklen nævnes et par eksempler på Andersens forgængere og samtidige, og desuden diskuteres hans indflydelse på Harald Bergstedt (‘Storegrisen’) og Dines Skafte Jespersen (‘Troldepus’-serien).