Jules Massenet was exuberant in his response to the music of Edward MacDowell: “Que j’aime les oeuvres de ce jeune compositeur Américain MacDowell! Quel Musicien! Il est sincère et personnel – quel poète – quelles exquises harmonies!”[1] These personal and poetic qualities are nowhere more evident than in the Moon Pictures, an early work, which MacDowell based on five stories from Hans Christian Andersen’s Picture Book Without Pictures.

Andersen’s Picture Book Without Pictures, or Billedbog Uden Billeder, was first published in Denmark in December 1839. The complete work, a little masterpiece, consists of an introduction and thirty-three stories.[2] The 1955 English translation by R. P. Keigwin was published on the occasion of Andersen’s one hundred fiftieth birthday, April 2, 1955, by the Andersen Museum, Odense, Denmark, and Berlingske Forlag – Copenhagen. Keigwin’s title, Tales the Moon Can Tell, supplanted the original title, Picture Book Without Pictures, which then became the subtitle. The poetic style of the more recent title pervades the entire translation, creating a rare and beautiful book.[3]

Andersen’s statement from the introduction to his stories reflects the richness of his imagination and invites further treatment by others: “A great painter of genius, some poet or musician, may make more out of them if he wants to.” MacDowell wanted to. A painter and poet himself, he responded naturally to the invitation. He could set them to music because there was an aesthetic affinity between Andersen and himself. Just as Andersen’s literary concept involved visual, poetic, and musical suggestion, so did MacDowell’s musical concept involve literary, visual, and poetic suggestion.[4] Within this broad spectrum of aesthetic components the visual component was to become a focal point for MacDowell’s Moon Pictures as it had been for Andersen’s Picture Book.

Perhaps MacDowell knew it was Mendelssohn’s Songs Without Words, music they both admired, that had inspired Andersen to write Picture Book Without Pictures.[5] By this means Mendelssohn had inadvertently set in motion a sequence of related works based on imagery and verbal paradox. MacDowell’s response to these precedents was to draw yet another parallel for the continuum: sound pictures without pictures. What better design for their use than to cast them into four-hand form so that he and his new bride, Marian Nevins MacDowell, could enjoy them together? Could they have read the Picture Book together in those Frankfurt-Wiesbaden years? Gilman relates their frequent reading “aloud in the evening – fairy tales, of which he was devotedly fond.”[6] The duet genre held a further appeal. A virtuoso pianist himself, MacDowell often seemed to prefer and deliberately choose a non-virtuoso composing style, sometimes even eliminating virtuoso passages from his scores.[7] Duets without virtuosity could be fun in the domestic scene.

Thus it was that in 1884 at Frankfurt, during a period of his life devoted to composition, to launching his career, and to enjoying Europe, MacDowell began the Moon Pictures. The exact date of completion is unknown. A late 1885 date is possible, given MacDowell’s revisionist tendencies, his financial need to publish promptly, and the 1886 publication date. If this was in fact the case, MacDowell would have been twenty-five and the locale Wiesbaden.[8] His original orchestral sketches for Opus 20 and Opus 21 were set aside; Opus 20 became Drei Poesien, his first essay in duet form, and Opus 21 the Mondbilder.[9] Duets became the order of day.[10] Perhaps he played them with Louise (L. E.) Nevins, his wife’s cousin. At any rate, his dedication, “zur freundlichen Erinnerung,” is to her.

One can speculate about a possible connection between the Moon Pictures and an 1885 letter from the great Venezuelan pianist, Teresa Carreño, to MacDowell. Her influence dates from his youthful pre-European years. As one of his early piano teachers, she prodded “Eddie’s” parents to take the sixteen-year-old to the Paris Conservatory for study. More than any other pianist she championed his cause in her own performances and through her contacts with the musical world. MacDowell’s letters to Marian in the Frankfurt-Wiesbaden period contain numerous references to “Teresita” in connection with his career.

The pieces were already in process and possibly completed when she wrote him on August 18, 1885: “It may be that you think I have taken a trip to the moon … It is high time I should inform you, that glad as I should be to spread my reputation as far as I can, and also add to yours the laurels and praise that the ’Mooners’ would certainly bestow upon you after hearing the Hexentanz or any other of your own ‘productions,’ (which of course I would have played had I gone up there), my ambition has not reached that point.”[11] It is interesting that her imagery apparently occurred independently, although further research may establish a connection.

The Andersen tales MacDowell chose are: The Hindoo Maiden; Story of the Stork; In the Tyrol; The Swan; and Visit of the Bears, titles Keig-win has changed in his translation to: The Indian Girl; The Little New Brother; Post-horn and Convent-bell; The Exhausted Swan; and The Dancing Bear. MacDowell created a cycle of character pieces out of the five contrasting tales. They are related, unified, and made into a cycle by the Moon Pictures concept, their brevity, their ABA form, the recurrence in the last piece of the opening tonality, and their suggestive style, but they do not compose a musical cycle in the sense of being thematically interrelated. Most of them are suggestive in an implicit, impressionistic sense, the exceptions being the more explicit, imitative suggestion of bell and horn motifs in In the Tyrol and the bear motif in Visit of the Bears.

MacDowell’s own statement that “it is in the power of suggestion that the vital spark of music lies” is a key to understanding his style. The specific musical means employed to create suggestion vary from piece to piece. In the Hindoo Maiden it is not only the occasional modal flavor which implies a Hindu setting, but also the sinuousness of melody, harmony, and rhythm. The Swan, perhaps the most vividly pictorial of the five tales, is the best example in this set of MacDowell’s implicit style. Suggestion indeed abounds. The absence of a secondo part for the first sixteen measures and the lightness of texture throughout suggest transparency of air and water. Long phrases of stepwise melodic progressions borne on long sustained notes, legatissimo, suggest gliding – of moon and swans. Pitch descends; the swan sinks. A low poised pedal point suggests the peaceful lake on which the swan rests and breathes a short tenor melody, a graceful, undulating line, hauntingly fragile. The rising sequence of the swan’s melody suggests preparation for flight. The beginning in e minor, andantino calmato, suggests the “dead calm” of the atmosphere; the G Major ending the renewal of the swan’s strength. The spiritual image of the swan is painted in the language of musical impressionism.

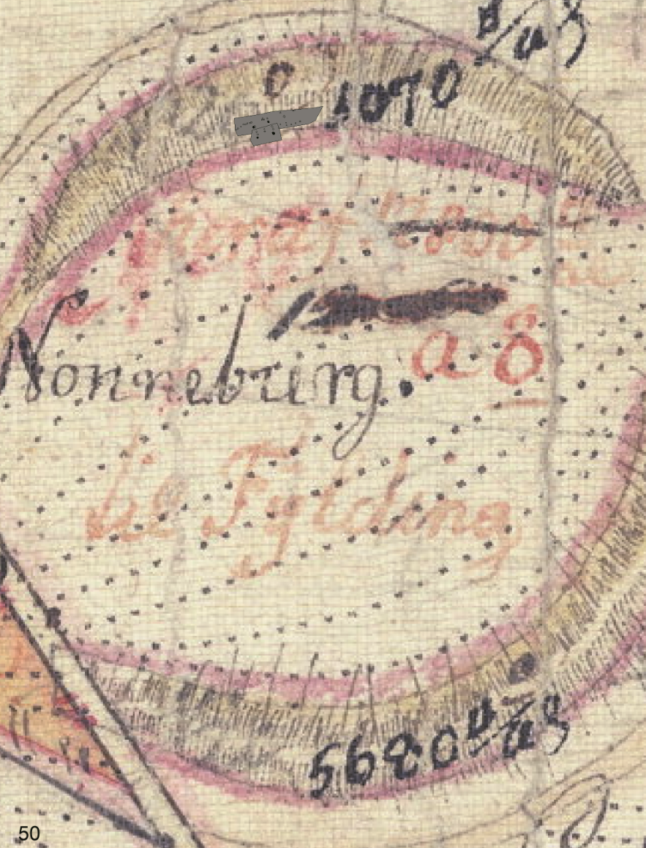

The Moon Pictures cycle, published originally in 1886 by Julius Hainauer – G. Schirmer, contained German titles only and the plate number J.275H.[12] This first edition with its subsequent issues is the only officially recorded edition to this date. A later, but early and undated version by the same publisher, presumably a second edition bearing plate number 19740c, is the source of my examples. Its existence appears to be virtually unknown. Perhaps because of MacDowell’s post-European controversies with publishers, including Hainauer, over publishing rights, it was withdrawn by the composer from publication. This would explain its absence from Sonneck’s Catalogue and Angell’s Supplement to Sonneck’s MacDowell Catalogue (1942). One can be sure its first printing occurred sometime between 1886 and 1898, no later than 1898 since in that year Julius Hainauer left his American agent, G. Schirmer, to make a joint publishing arrangement with Breitkopf and Härtel.[14] At this writing G. Schirmer of New York has no plate number 19740c.

That MacDowell was pleased with Hainauer’s musical and artistic standards is apparent in his January 2, 1884 letter to Marian. He says, in referring to a Hainauer publication of unnamed pieces prior to that date, “I think he pays me a great compliment in bringing them out in such fine style.”[15] Both versions of the Moon Pictures, including general format, orthography, and decorative features, have style. Both are examples of MacDowell’s cosmopolitan use of Italian expression marks, an early period characteristic he later abandoned. The only changes in the score of the 19740c edition are: the addition of English titles; the resulting oversize page format; and a minor improvement in orthography. On page eight, second staff, the terminology is changed from rallentando to poco allargando, which synchronizes the secondo and primo part markings. MacDowell himself may have revised the original edition in this manner since the differences between the two editions are typical of the kinds of differences that generally occur in his revisionist process.

Both editions of the Moon Pictures are currently out of print. A new edition combining the best features of the early editions with the Andersen – Keigwin tales could be an appealing contribution to the piano duet literature.