The nineteenth-century romantic theatre, for H.C. Andersen a dual source of rich inspiration and intense despair, was succinctly described by the German scene designer K. F. Schinkel as „eine lebende Bildergallerie“ — a picturesque and changing panorama of the dismal caves and crumbling dungeons of Gothicism, the familiar landscapes and recognizable streetcorners of the vaudeville genre, the ethnographic views and strange customs of exoticism. The popular interest in what might be called „the theatre of the exotic,“ in which scenery, tableaux, and costumes conveyed a sense of the far-away and the fantastic, was especially strong. This interest was obviously not restricted to the playhouse alone but manifested itself in a variety of other ways, one of which is represented by Andersen’s own vivid descriptions and charming sketches of local color and exotic customs in a work like En Digters Bazar. In the realm of theatre, however, illustrations which reliably depict the appearance of the colorful characters who populate the „exotic“ plays and operas of H.C. Andersen are extremely rare. Hence, for this reason alone, the discovery of a complete set of twelve costume sketches drawn for Andersen’s operatic adaptation of Carlo Gozzi’s fantasy II corvo, Ravnen, deserves some attention. In addition, these drawings serve to shed new light on the exotic style of costuming so popular with Royal Theatre audiences in Andersen’s time.

Exotic theatrical dress was an ingredient of the utmost importance in the atmosphere of such romantic milieu pieces as H.C. Andersen’s Mulatten, Maurerpigen, Brylluppet ved Como-Søen and Ravnen. For each of these four productions, carefully detailed costume lists are preserved which testify to the degree of attention devoted to this aspect of the scenic picture. The broad tradition of exotic costuming was, of course, deeply rooted in the eighteenth-century theatre. Indeed, developments during the first half of the nineteenth century frequently showed a degeneration rather than an improvement in unity and harmony of style. In this connection, Andersen’s criticism of the celebrated actress Johanne Luise Heiberg’s wretched costume as the Greek princess in Henrik Hertz’s romantic drama Svanehammen (1841) comes to mind: „she was a schoolgirl, and no half fairy from Greece,“ he remarked tersely.[1]

H.C. Andersen’s lively interest in the theatrical possibilities represented by exotic costuming received expression already in the composition of his first opera libretto, Ravnen, produced with a score by J. P. E. Hartmann in 1832. This delightful operatic fantasy represents perhaps the best illustration of the exotic tradition in Andersen’s Royal Theatre productions, chiefly because of twelwe hand-colored costume designs which have come to light in the Royal Theatre Library. These sketches, which have lain unnoticed in the theatre’s archives for more than a century, were drawn for the revival of Ravnen in 1865, but the style they represent corresponds largely to that of the original production in 1832. The fact that these drawings are reliable and were actually followed in practice may be conveniently verified through a comparison with the Royal Theatre’s journal of tailor and seamstress payments.[2]

In addition to the Ravnen sketches, a number of other unpublished sources illustrate the process through which the exotic characters of H.C. Andersen’s imagination were transferred from paper to the stage. It was obvious from the very beginning that the costuming of Ravnen would involve the Royal Theatre in considerable expense. A letter dated October 5, 1832 from the redoubtable Doctor-actor-wardrobe supervisor J. C. Ryge to the theatre management is so illuminating regarding this aspect of theatre practice that it deserves to be quoted at length:

To the high Management of the Royal Theatre:

With respect to costuming, the fantastic opera Ravnen is a very difficult and costly piece to stage at the Royal Theatre. For, despite the fact that the theatre’s wardrobe supply contains costumes from [Simone Mayr’s opera] Lanassa, [Theéaulon’s fantasy] La clochette, and [F. Kuhlau’s opera] Lulu which could be used, far more changes would be necessary in Ravnen, both for the chorus and ballet corps, for which these costumes are far from sufficient. Since time is now extremely short … I must with deepest respect request the high management to excuse me from preparing a most humble and detailed proposal concerning which new wardrobe pieces it will be necessary to procure, a proposal which I could hardly deliver in eight days — but out of confidence in my judgment, experience, and well-known thriftiness [!] to allow me to make the necessary purchases as needed, as well as from next Sunday on to employ as many extra workers, both tailors and seamstresses, as I may require. That I at a later time both shall and can give a proper, and I trust complete, account of all that I undertake in this connection is a matter of course …

With deepest respect,

J. C. Ryge Dr.P.S. Since the costuming will be Indian, it is highly probably that much of the purchased material can be used again in [Auber’s] Le Dieu et bayadère.[3]

Despite the parsimonious Dr. Ryge’s economical efforts to utilize costumes from previous exotic productions, it became necessary to produce a large number of new exotic, oriental costumes for Ravnen and, as the wardrobe supervisor foresaw, costume expenses proved to be considerable. The „complete account“ which Ryge mentions in his letter was submitted on February 12, 1833, and it fully confirms the fact that costuming was frequently the largest single production cost at this time. Wardrobe expenses for Andersen and Hartmann’s opera totalled no less than Rdl. 1172.2.7, while staging amounted to Rdl. 235.2.3., the few rehearsals cost only Rdl. 68.2.4. (of which more than 60% was paid to the stagehands), and book and music, including Andersen’s and Hartmann’s combined fee of Rdl. 567.3.6, came to Rdl. 961.4.9.[4]

The care and expense devoted to the costuming for Ravnen were, however, repaid by excellent results. A letter written by H.C. Andersen four days after the opening indicates that the author was well satisfied with this aspect of the production:

The costumes are indescribably beautiful; in particular, the four dancing girls were quite enchanting (they wore red silk trousers and white gauze dresses), there were twelve Knights of the Sun in white costumes. Golden helmets with a sun and a gold shield with the sun emblem. They were impressive.[5]

When Andersen’s rewritten version of Ravnen was revived in 1865, costuming was again a key production problem. H. P. Holst, who staged the opera, consulted the author about which costumes to use; in a letter dated January 2, 1865 Andersen wrote: „Holst wanted to know in what costumes the opera should be played, and I immediately informed him. So I hope that my Raven will soon fly into the repertoire.“[6] Presumably on the basis of the (unfortunately lost) reply from Andersen to Holst, a costume proposal and the twelve costume designs reproduced here were prepared.[7] Although the commedia dell’arte figures originally borrowed from Gozzi were given new names and new outward appearances by Andersen for the 1865 revival,[8] most of the characters in the sketches correspond directly to their counterparts in the 1832 production. For the revival it was necessary to produce a total of 135 new costume pieces.[9]

While the letters and other documents just described provide a backstage view of the process by which the exotic costumes for Ravnen were procured, the actual costume lists and designs illustrate fully the realization of H.C. Andersen’s characters on the stage. In spite of Ryge’s request in the letter cited above, he was apparently not excused from preparing the customary, detailed costume proposal, since such a proposal from his hand, dated October 26, 1832, is to be found in the Royal Theatre’s archives. Compared with this document, an undated costume list for H. P. Holst’s 1865 production is far less detailed and informative, and must be supplemented with information gathered from the tailor protocol.

Both in the staging and the costuming of Ravnen, stylistic confusion and inconsistency marred the scenic picture. Gothic and exotic elements were mixed freely, particularly in the 1865 revival where costume items classed in the wardrobe guide as „European, from older times“ and as „African, Moorish“ were combined indiscriminately. There was more than a little truth to the remark made by the sarcastic reviewer for Folkets Avis (April 25, 1865) about seeing Teuton knights who wandered through settings with Moorish minarets from which Christian churchbells chimed!

Costumes for the 1832 production of Andersen’s opera seem in many cases to have been both more atmospheric and more consistent in style than those for the later revival. Hence the nine halberdiers in the earlier production — the impressive Knights of the Sun so enthusiastically described by H.C. Andersen — called a particularly striking impression with their golden helmets and breastplates, tunics and pantaloons of white twilled shirting trimmed with red chintz and golden tassels, sashes of red chintz with golden fringes, small golden sabres on red strings, and oval shields with a golden sun on a field of red.[10] These red and gold costumes, sparkling in the dim glow of the oil lamps illuminating the stage, undoubtedly presented a far more picturesque and exotic sight than did the fourteen halberdiers and sixteen warriors in the 1865 production. These later halberdiers (Fig. 1) wore rather conventional attire consisting of colored berets and tunics, red pantaloons, swords, and turned-down brown boots.[11] The costume worn by the sixteen warriors (Fig. 2) consisted of a belted blouse over a tight-fitting tricot, providing more of a Nordic than an Indian impression.

Similarly, the two types of courtiers — sixteen in all-appearing in the original production seem to have been far more flamboyant and exotic in their attire than the corresponding members of Millo’s court in the later version, pictured in Fig. 3 and 4. In 1832 the courtiers wore colorful oriental bonnets of chintz or merino, pearl necklaces, shoulder drapery of striped muslin or shawl cloth, colored or flowered caftans, gaily striped sashes with gold tassels, light, striped tricots, and gold, laced boots. It is generally symptomatic in contrasting the two Ravnen productions that, while in the original version the eight sailors who row Jennaro and the abducted Armilla onstage wore exotic, Cingalese costumes borrowed from Galeotti’s comic shipwreck ballet Afguden paa Ceylon, the same sailors in 1865 were dressed in tunics, as seen in Fig. 2, borrowed chiefly from Bournonville’s decidedly Nordic ballet Waldemar.

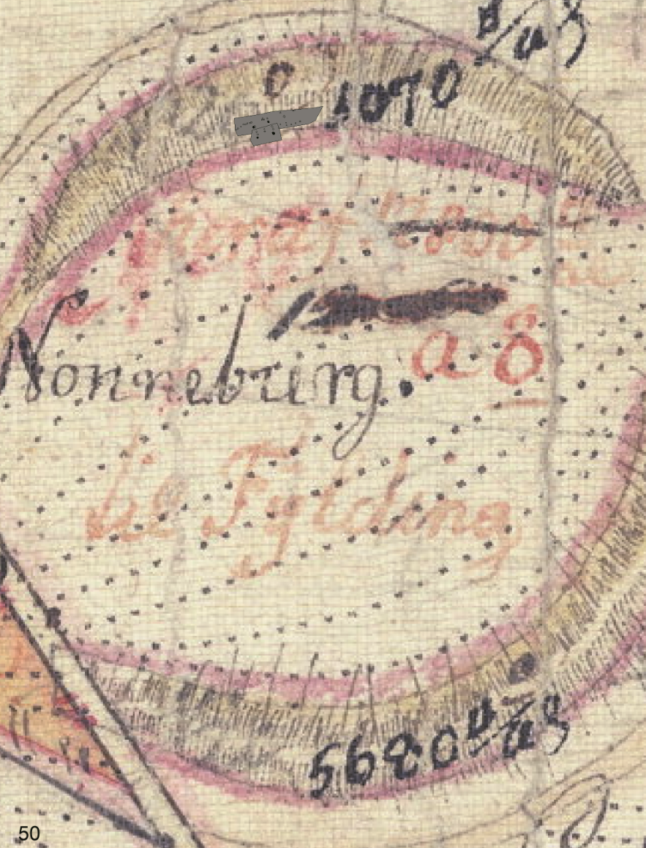

The stage appearance of H.C. Andersen’s fantastical figures in Ravnen remained, however, basically similar in both productions of the opera. In the picturesque opening scene in the mountain cave of Norando, the mighty magician is surrounded on three sides by a fantastical chorus of fire, earth, and water spirits. These preternatural beings are in frenzied activity, and their movements contribute visually to the picturesqueness of the scenic display. Three charming, hand-colored sketches provide a vivid impression of Andersen’s elemental spirits. The chorus of gnomes, or earth spirits, wore gray tunics and brass bands on head, arms, and legs (Fig. 5). The winged salamanders appeared entirely in red in the costume shown in Fig. 6. The water nymphs were clad in delicate, silvery blue frocks painted with scales (Fig. 7). The comparatively detailed promptbook for H. P. Holst’s staging of Ravnen in 1865 is informative about the manner in which these fantastical figures were grouped into colorful attitudes and tableaux within the romantic stage picture. Thus, when Deramo brings the news in the opening scene of the abduction of Armilla, Norando’s daughter, the elemental spirits „press closer, terrified“ on the line „And she has fled with him—?“ At Norando’s thunderous retort, „Bleed for revenge! In torment end!“ the salamanders rush to the foreground swinging their torches and the earth spirits brandish their hammers. At the final dramatic exclamation — „Ha, revenge and death!“ — the spirit chorus spreads to all sides at the sound of „a terrible thunderclap,“ as their dread master Norando sinks into the floor! H.C. Andersen was understandably delighted with these picturesque and dramatic effects, and an enthusiastic sketch which he drew in the childhood album of actor Otto Zinck, now in the H.C. Andersen Museum in Odense, provides a charmingly impressionistic illustration of the cave scene as it appeared in the 1832 production. (Fig. 13)

Unfortunately no costume designs survive to indicate the appearance of the two most essential groups of preternatural beings in Andersen’s Gozzi adaptation, the three mermaids who appear to Jennaro to recite the curse of Norando and the thirteen fearful vampires whom Jennaro encounters outside his brother Millo’s bedchamber. Ryge’s costume list from 1832 provides us, however, with concrete descriptions of both groups. The mermaids could obviously not appear in their traditional topless attire; instead, they wore a decorously stylized costume consisting of a flesh-colored silk jacket and a light blue skirt, together with long, hanging hair spangled with white pearls. The terrible vampires were dressed in gray headgear and tricot and boasted gray bat-wings; there is, however, no evidence that they wore the toothless mask with thick rubber lips which H.C. Andersen had envisioned in his stage directions.[12]

The Eastern costumes of the leading characters were particularly effective and picturesque in the earlier production. The male costumes were characterized by richly colored and ornamented shoulder capes and oriental caftans, decorative tasseled sashes, long tricots, and turbans with pearls and gold. For the heroine Armilla’s two costumes the basic elements were a white bobbinet veil, a short Eastern dress, a long tricot, and a colored, fringed sash — the general style is illustrated in the dancing-girl’s attire in Fig. 8. For Armilla’s first appearance, alighting from a gondola after having been kidnapped by Jennaro, her costume was lavishly adorned and embroidered with silver, while a later costume was trimmed with gold. In the 1865 revival, Armilla’s first costume, which included a light blue, satin cap trimmed with gold, a red damask apron, a gold satin skirt, and a white silk scarf, was classified as „African, Moorish,“ while her second costume, a long white satin gown, was incongruously European in style.[13]

By far the most lavish examples of exotic attire in H.C. Andersen’s Ravnen were the costumes worn by Millo, the lordly ruler of Frattom-brosa for whose sake the lovely Armilla has been abducted. Ryge’s costume list contains a wealth of information about the style of Millo’s splendid and decorative costuming. For example, his second costume included an oriental, red velvet headgear trimmed with gold, pearls, and precious stones and decorated with a bird of paradise. Over a light satin caftan trimmed with matching red velvet and a golden border, the king bore a shoulder cape of red shawl-cloth and a necklace of pearls. The costume was rounded off by a red velvet sash with gold fringes, and gold pantaloons patterned with red velvet and thin gold stripes.

Although the 1865 costume list provides no comparable information about Millo’s costume, other than the laconic remark „black beret with gold,“ the corresponding costume drawing conveys a clear impression of this character’s appearance. In this colored sketch (Fig. 11) the round beret is black with golden design, the loose shoulder cape is brown with a gray border, and the tunic is blue with gold trim. The costume is completed by the colorful, tassled sash, a loose red undergarment and pantaloons, and brown slippers.[14] By comparison, Millo’s costume in 1832 appeared far more flamboyant in its use of pearls, gold, and feathers, and more harmoniously colorful in its carrythrough of the scheme of red velvet and gold than the somewhat plainer counterpart utilized in 1865. By the time of the later performance, at the close of H.C. Andersen’s career as a dramatist, the connection with the older eighteenth-century tradition of the grandly exotic „Eastern potentate costume,“ with its waving plumes, glittering stones, and richly dyed materials, had obviously grown much weaker.

One of the principal changes which H.C. Andersen made in his revision of Ravnen was the substitution of the commedia dell’arte figures originally taken from Gozzi. In the 1832 production, however, these figures appeared in festive costumes bearing some resemblance — at least in color scheme — to the traditional attire of the Italian masked comedy. Hence Pantalone wore a costume which gave an overall impression of characteristic black and red, consisting of a black hat and long cape with short sleeves, a red jerkin, reddish knee-breeches, red stockings, yellow slippers, and the traditional dagger. Brighella was appropriately dressed in cape, jerkin, and long trousers all in white, decorated with the familiar horizontal stripes of green velvet braid, and supplemented with a gray hat and gray shoes. Truffaldino appeared in a form of Harlequin costume, with cape, jerkin, and breeches consisting of the time-honored patchwork in black and white. He wore a patched black, high-crowned hat with black feather, a wide white collar, black sash, and striped stockings. Tartaglia was clad in a version of the Captain costume, with broad ruff collar, a brown silk cape, a brown sash, and long, gray gaiters, combined with green plaid knee-breeches, jerkin, and cap. As accessories this bragging soldier bore yellow, cuffed gloves and a military shoulder belt with a so-called „Crispin rapier.“ Smeraldina, on the other hand, appeared in a conventional exotic costume consisting of a bodice and skirt of green embroidered silk, a yellow sash, long yellow trousers, colored Indian slippers, and a large red and white turban. The costume list gives no indication that any of Andersen’s commedia dell’arte figures wore masks for the production.

Unfortunately, no illustrations survive of these colorful, nineteenth-century editions of the masked comedy types. Because H.C. Andersen felt that the commedia figures had been poorly received and misunderstood in the original production of Ravnen, he decided to substitute other characters for them in the revival. Although the appearance of these substituted characters is not described in the costume list, the final costume sketch in the series depicts Kløerspaerrude (literally Clubs-Spades-Diamonds), the buffoon role created by Andersen to replace Brighella and Truffaldino. Fig. 12 is a delightful illustration of this gaudy, playing-card jester’s costume; the figure in the picture is unmistakably Ludvig Phister, the great Danish comic actor who appeared in the part. The colorful costume design indicates a green hat with red feather, orange hood and collar, and a cream-colored tunic dotted with orange diamonds and black clubs and spades, under which Clubs-Spades-Diamonds wears a tricot in which the right sleeve and left leg are red, and the left sleeve and right leg are blue.[15]

This gallery of sketches for H.C. Andersen and J. P. E. Hartmann’s operatic fantasy, taken together with the appropriate documents from the Royal Theatre archives, conveys a rich, vivid impression of the exotic style of costuming that played so essential a part in the romantic theatre’s lebende Bildergallerie. H.C. Andersen’s text for Ravnen was influenced and moulded by two equally significant factors: Hartmann’s melodious romantic score and the traditions of the theatre of the exotic. Despite some obvious stylistic inconsistencies in the two productions of Ravnen, a certain unmistakable charm nevertheless pervades this style, totally independent of the question of „historical accuracy.“ Particularly the original 1832 production, with its striped and flowered chintz and shawl-cloth decked with pearls and gold and its colorful array of fantastical figures, seen in the flickering glow of the dim stage lighting, must have made a delightfully festive and theatrical impression on the audiences of the time.